Command Line

You're interacting with your server using a Terminal application, which accepts text commands that you type into it. This is sometimes referred to as a command-line interface (CLI).

The Terminal application itself gives you access to a shell program that runs on the server. This program—bash most commonly, or zsh on recent Macs—allows you to give commands to the computer via that command-line interface.

Let's go over some of the commands that are available to you in the command line. The more you work in the terminal, the more you'll have occasion to use these. You'll know that your Terminal, running a shell, accepting input via the command line, is ready for input when it gives you a prompt:

$indicates that you're a user running the bash shell%indicates you're running the zsh shell#indicates that you're running commands as root (not recommended at the beginning)

Important concept: File paths

There are two ways of referring to the location of a file in the computer's file system: absolute path and relative path.

- Absolute path

The absolute path for a file is given relative to the root directory/. A "notes" file stored on my Desktop would be indicated by the absolute path/home/ubuntu/Desktop/notes.txt. That path is unique, and will always refer to that file, regardless of where it is used. - Relative path

The relative path for a file is given relative to wherever I currently "am" in the filesystem, ie. my working directory. If I wanted to list the contents of the notes file, the command I give would depend on where I am in the filesystem.- If I'm on the Desktop I would say

cat notes.txt - If I'm in the

ubuntuhome directory I would saycat Desktop/notes.txt - If I'm somewhere else in the file system I might say

cat ~/Desktop/notes.txt

- If I'm on the Desktop I would say

Either system of addressing will work for most purposes. It's usually just a question of what is most convenient.

Useful shell commands

pwd

What it does - Prints the working (current) directory

Example of use, with output

$ pwd /Users/rwhite/DocumentsOther info - Not used much once you get more experienced, but always useful (especially as you're learning) to identify where in the filesystem you're currently locatedls

What it does - lists the contents of a directory

Examples of use

$ ls # lists the contents of the current directory $ ls .. # lists the contents of the directory one level up $ ls -a # lists all the contents of the current directory, including "hidden" files # (the ones that start with a .) $ ls -l # lists the contents of the current directory in long format $ ls ~ # lists the contents of the home directory $ ls -R # lists the contents of the current directory recursively # (including the contents of directories below this one)Other info - Not used much once you get more experienced, but always useful (especially as you're learning) to identify where in the filesystem you're currently locatedcd

What it does - Changes your location in the filesystem to a different Directory

Examples of use

$ cd .. # changes to the directory above the working directory $ cd / # changes to the root directory $ cd ~ # changes to the user's home directory $ cd ./subdirectory/subdirectory # changes to a directory below the current one $ cd ../../directory # changes to a directory in a different part of the filesystemOther info - Not used much once you get more experienced, but always useful (especially as you're learning) to identify where in the filesystem you're currently locatedcat

What it does - Displays the contents of a file

Example of use, with output

$ cat hello_world.py #!/usr/bin/env python3 print("Hello, world!")Other info -catis useful for quickly displaying the contents of a small file. If you want to search through a larger file, you're probably better off usingless(see below). You can also usenano, although you run the risk of accidentally changing the file then.mkdir

What it does - Makes a new, empty, directory

Example of use

$ mkdir new-project

Other info - If you've got a new project you're about to start work on, a typically sequence is usingmkdirto create the project directory, and thencdto change into that project directory to begin working.sudo

What it does - "SuperUser DO" elevates privileges for accomplishing some tasks

Example of use, with output

$ sudo apt update Hit:1 http://ports.ubuntu.com/ubuntu-ports focal InRelease Get:2 http://ports.ubuntu.com/ubuntu-ports focal-updates InRelease [114 kB] Get:3 http://ports.ubuntu.com/ubuntu-ports focal-backports InRelease [101 kB] . . $ sudo shutdown now Connection to 192.168.7.207 closed by remote host. Connection to 192.168.7.207 closed. $Other info - Not all users on a system have the ability to use thesudocommand. Obligatory XKCD reference.cp

What it does - Makes a copy of a source file to a destination file

Examples of use

$ cp /etc/netplan/50-cloud-init.yaml /etc/netplan/50-cloud-init-original.yaml cp: cannot create regular file '/etc/netplan/50-cloud-init-original.yaml': Permission denied $ sudo cp /etc/netplan/50-cloud-init.yaml /etc/netplan/50-cloud-init-original.yamlOther info - In the example here, before modifying the file we've made a copy of the original, to be reverted to in the event we make a mistake in editing that file. The first we failed because we needed to have elevated privileges. Usingsudogave us those privileges.mv

What it does - Moves a file from one directory to another and/or renames the file

Examples of use

$ mv hello_world.py ~/archive/ # Moves the file from the current directory into the archive directory $ mv hello_world.py goodbye_world.py # Moves the file from an old filename to a new filenameOther info - A common beginner mistake is to issue anmvcommand likemv hello_world.py ~/archive. If the directoryarchiveexists, the file will be moved into it as desired, but if that directory doesn't already exist, thehello_world.pyfile will be moved to the home directory (~) and renamed asarchive, which is probably not what we intended. By adding an extra forward-slash at the end of "archive", we are indicating that we want the file to go into the directoryarchive. If that directory doesn't exist, we'll get an error message and we can fix our mistake by creating that directory before continuing with themvoperation.rm

What it does - Removes files and directories

Exampled of use

$ rm hello_world.py # removes the indicated file $ rm *.py # removes all of the files with extension .py $ rm -r * # removes all of the files in the current directory, # recursively removing files in the directories below as wellOther info - Thermcommand should only be used with extreme caution; there is no recovery once you've deleted a file or directory.less

What it does - Displays a file one terminal page at a time

Example of use

$ less filename

Other info - Once the file is opened you can navigate it with a series of simple commands:q- quit (close file)f- moves forward one pageb- moves back one pagegg- moves to beginning of fileG- moves to end of file/- enter expression to search for, hit [Enter] to completen- find next occurrence of search expressionN- find previous occurrence of search expression

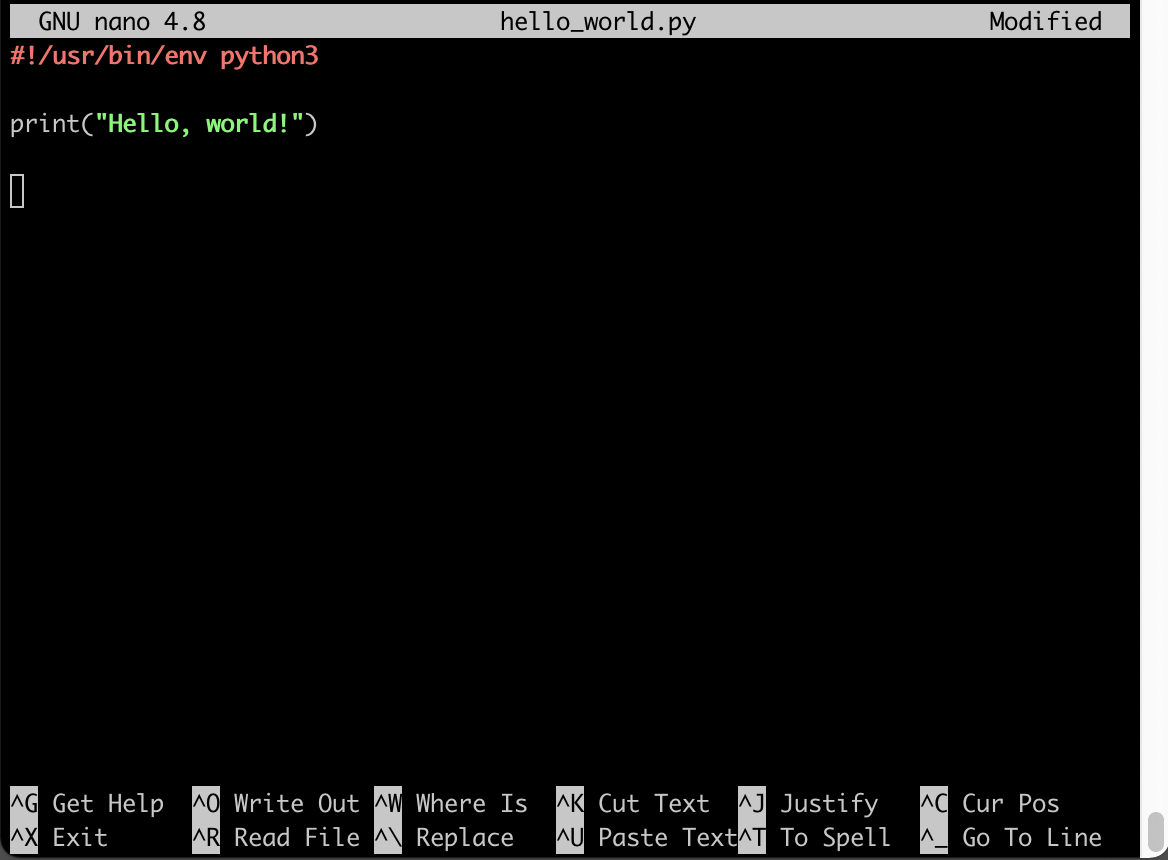

nano

What it does - Uses the nano editor to edit a file

Example of use, with output

$ nano hello_world.py

Other info - There are more powerful text editors, but nano is the perfect command-line editor to get you started working in the Terminal. See Intro to nano for more info.

Other info - There are more powerful text editors, but nano is the perfect command-line editor to get you started working in the Terminal. See Intro to nano for more info.

man

What it does - Displays the manual for a given command

Examples of use

$ man less # Gives help on using the less command $ man sudo # Gives help on using the sudo commandOther info -manpages use the same navigation system thatlessuses.find

What it does - finds files in the filesystem

Examples of use

$ find . -type f -iname "hello" # Begins looking in the current directory (.), # looking for a file (f) called 'hello' $ find . -type f -iname "*hello*" # Looks for a file with 'hello' # anywhere in the name. The asterisks are an example of 'globbing', # where the '*' acts as a kind of wildcard for any expression $ find . -type d -iname "*Doc*" # Looks for a directory with 'Doc' # anywhere in the name $ find ~ -type f -size +100M # Looks starting in the home directory # for any file that is larger than 100M in size $ find ~ -type f -mtime -7 # Looks starting in the home directory # for any file that was changed less than 7 days ago $ find ~ -type f -mtime +30 # Looks starting in the home directory # for any file that was changed more than 30 days agoOther info - The find command is extraordinarily powerful, and can be used in lots of different ways.grep

What it does - searches files looking for patterns (regular expressions). "grep" stands for "global regular expression print"

Examples of use

$ grep -ri password project # Searches recursively, insensitive to case, # for the expression "password" in the "project" directory $ grep -ri "rw.*@crashwhite.*" project # Searches in the project directory for # any expression that starts with 'rw" and # has '@crashwhite' connected to itOther info - Note that the ".*" used in these regular expressions is differnt from the "globbing" wildcard we used with thefindcommand. Regular expressions are one of the most important and powerful pattern matching tools in computer science--once you get to know them a little better, you'll love them!